A Giving Journey

IT ALL STARTED WITH THE RIM OF A BASKETBALL HOOP

In 2007, George Grody, teacher of markets & management at Duke University, member of the Duke Athletics Board, and a 1981 alumnus of Duke, entered a two-person online auction bidding war. The prize was the 1992 NCAA Men’s Basketball Championship final game rim, and the proceeds were earmarked for Duke Children’s in memory of two young girls who were treated there for cystic fibrosis.

As a Duke alumnus and avid fan, Grody attended the game, traveling to Minneapolis from his then-home in Taiwan, and watched the Blue Devils clinch the championship. The rim would be nostalgic memorabilia, so he set a $2,500 spending limit.

The last-minute bidding crept up incrementally, and in the final seconds, the winning bid of $17,500 came in. Grody came up short, but it was the loss of the two young patients that stuck with him.

“Every time I refreshed the site to make a new bid, I would see the pictures of these two young girls,” Grody says. “Seeing them and reading their story impacted me.”

In that moment, he decided to become a Duke Children’s donor—a choice that launched him down a path of giving that recently topped $1 million.

THE JOURNEY TO MAKING A DIFFERENCE

Grody’s long-term giving journey had been two-pronged: personal contributions and extensive fundraising efforts. It all started with simple annual gifts. After a few years, Karen McClure, at the time the director of special programs and Children’s Miracle Network Hospitals with Duke Children’s Development, encouraged him to make a multi-year pledge and invited him to join the Duke Children’s Development Board.

Grody accepted, and his twelve-year stint included four years of serving as board chair. During his tenure, he turned the group into an active board that thoughtfully pursued ambitious fundraising goals for the hospital.

Since then, the constant motivation, he says, has been improving young patients’ lives.

“When you see children in the hospital, they’re innocent. They don’t deserve any disease they’re battling,” he says. “When you save a child, you’re saving a whole life—sometimes 70 or 80 years.”

His opportunities to impact more lives blossomed in 2008, after he left a long career at Procter & Gamble. His numerous roles with the company had taken him all over the world, but he was excited to return to Durham and Duke as a teacher and special assistant to Duke’s athletics director. Through these roles, he developed strong ties to many teams and encouraged student-athletes to use their talents to benefit pediatric patients. The teams had been involved with Duke Children’s casually through activities like visiting patients in the hospital, but Grody deepened that relationship, encouraging direct fundraising efforts and more intentional engagement.

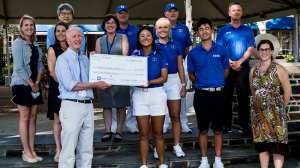

In 2018 Virginia Elena Carta, then a senior on the woman’s golf team and NCAA golf champion, was one of the first to ask for Grody’s help in designing a program. Together, they created Birdies for Babies, an initiative where donors make pledges for every birdie student- athletes make. Funds raised support the neonatal and pediatric intensive care units. The program, which involves both the women’s and men’s golf teams, is in its sixth season, and recently topped $100,000 in donations. To recognize these efforts, Duke named the Birdies for Babies room in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU).

But Birdies for Babies is only the tip of the iceberg. Grody, who committed to a large estate gift benefitting Duke Children’s, Duke Athletics, and Duke Libraries, also helped the baseball team launch K’s 4 Kids’ Cancer and Bases 4 Babies where donors make pledges benefiting cancer research and care for every strikeout or base reached during the season.

He also created programs to benefit older patients. By helping establish Fence for the Fight, a partnership between Duke Fencing and Duke Cancer Institute, an initiative which recently achieved $100,000 in funds raised, he helped raise money for adult breast cancer patients.

Grody’s efforts to improve patient lives extend beyond athletic partnerships. In 2017, he helped establish the Duke Children’s Prom (now Jodie’s Prom for Duke Children’s), an annual event that turns the Children’s Health Center lobby into a rocking dance floor for a night, and Duke students have volunteered to make the night special. The goal, McClure says, is making sure pediatric patients don’t forgo pivotal memories. “George has such a big heart. He wants the kids’ experiences to be as normal in as many ways as Duke Children’s can make them.”

BIRDIES FOR BABIES PATIENT IMPACT

The named space in the NICU may be the most obvious evidence that Birdies for Babies has helped patients. But the real impact is the improved resources available to providers, says Michael Cotten, MD, professor of pediatrics and neonatology division chief.

To date, the donations have paid for new training equipment for medical students, residents, fellows, and interdisciplinary teams. With simulation and training devices for neonatal resuscitation and intubation, the division can better prepare practitioners for NICU work.

Having the right tools and appropriate accommodations is vital to delivering the highest level of care to the youngest patients. However, securing them isn’t always easy. Donors like Grody play an important role in fulfilling those requirements.

“Every Duke Hospital care team has needs. But the existing budgets alone can’t meet every need, so philanthropy is crucial,” Cotten says. “People like George are the champions we need to get a little extra support. It’s game-changing, and it helps accelerate the delivery of the best possible care in the best possible environment for the babies and their families.”

SHAPING THE LIVES OF STUDENT-ATHLETES

As successful as Grody’s efforts have been in raising funds for Duke Children’s programs, he’s also instilling greater compassion and generosity in this generation of student-athletes. Through his long-standing relationship with Duke Athletics, Grody frequently meets with student-athletes and their families to discuss Duke’s myriad of

opportunities. That includes participating in the Duke Children’s-Duke Athletic Partnerships, says Lindy Brown, senior associate director of communications for Duke Athletics.

“When George talks to people, he gives off that vibe of how important it is to help others,” he says. “It just rubs off on the student-athletes and the coaches.”

As Grody encourages the student-athletes and partners with them to bring their ideas for giving programs to fruition, he’s teaching them the value of selflessly doing for others, says Debbie Taylor, senior associate director of Duke Cancer Institute and Duke Children’s Development.

“He’s teaching our athletes there are bigger things than the sports they play. He’s giving them a platform where they can make an impact by giving to others,” she says. “He demonstrates the idea that for those who have been given much, much is expected.”

McClure adds, “He helps the Duke students understand that often some of the greatest needs—the ones where they can make the biggest impact—are close to home.”

Ultimately, Grody says, his ongoing drive to create and maintain these programs stems from his internal belief that taking action—even something small—is the only way to bring about change.

“There’s a quote that I live by: ‘I am only one, but still, I am one. I cannot do everything, but I can do something. And because I can’t do everything, I refuse to not do the something I can do,’” he says. “I can’t cure cancer, but I can help raise some funds to give to the people that can cure cancer. I can’t save everybody. But I can save one person, two, or more people—people who may not have been saved if I didn’t just try to do something.”

Published as part of the Summer 2023 issue of Duke Children's Stories