The Mysterious Case of the $11 Million Benefactor

In an age when people share the details of their days on social media and you can learn almost anything about almost anybody with a few clicks, it is not easy to pass through a long life and leave behind as little public record as Swann Lee did.

She was an attorney based in Manhattan who worked for an investment banking firm for 30 years. She was married once, to a man who predeceased her by four decades, and had no children. When she died in July 2021 at the age of 99, she left no heirs. No obituary has surfaced.

As far as anyone can tell, she had no direct ties to Duke University. There is no record of her, or any relative of hers, having been enrolled as a student at Duke, employed as faculty or staff, or treated as a patient at any Duke clinic or by any Duke provider.

So, it came as a surprise to learn that Lee had left the bulk of her estate — some $11 million — to Duke.

Her bequest came with specific terms: it was to be used “solely for nutritional and laboratory research focused solely on preventive care and health maintenance” — not for medical treatment or disease cures.

“We don’t know why she picked Duke,” said Sarah Armstrong, MD, professor of pediatrics, founding director of the Duke Healthy Lifestyles Clinic and co-director of the Duke Center for Child Obesity Research. “But somehow, she found us, and we are grateful that she left this generous resource for nutrition research at Duke. We will put her philanthropy to good use.”

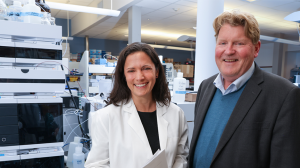

School of Medicine Dean Mary E. Klotman, MD, reached out to Armstrong and Chris Newgard, PhD, director of the Sarah Stedman Nutrition and Metabolism Center and founding director of the Duke Molecular Physiology Institute (DMPI), to develop a research project that could use a portion of the Lee estate gift to generate important data in keeping with the terms of the bequest.

The result is a new children’s health research project, co-led by Armstrong and Newgard, called “Nutrition and Obesity in Under-Represented Populations: Food Insecurity Research to Advance Science and Improve Health” — Project NOURISH, for short.

The Food Insecurity-Obesity Paradox

Co-led by Armstrong and Newgard, NOURISH is an innovative multi-disciplinary approach that combines clinical research and basic science research to explore what is known as the “food insecurity-obesity paradox.”

Both food insecurity — the lack of consistent access to healthy food — and child obesity have increased dramatically in recent years: approximately 12 million children (1 out of every 6) live in food-insecure households, and 14 million (1 in 5) children have obesity.

The paradox is that many of these are the same children: a scarcity of nutritious food is strongly associated with the development of obesity.

“Very young kids subjected to food insecurity often are at risk for obesity, which at first glance seems strange,” said Newgard, the W. David and Sarah W. Stedman Distinguished Professor of Nutrition. “Sarah and I came up with a project to try to learn more about food insecurity and its relationship to obesity, both at the pre-clinical and clinical level, and ultimately, we hope, to use what we learn to develop interventional strategies.”

The reasons for the counterintuitive association between food insecurity and obesity aren’t clear, although one factor may be that many of the foods available in quantity to families with limited resources tend to be calorie-dense but nutritionally poor.

What is well established is that the incidence of obesity is rising rapidly, and that childhood obesity strongly predicts adult obesity and associated health problems later in life, such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and high blood pressure.

And, Armstrong said, interventions designed to address either issue in isolation may unintentionally exacerbate the other: recommending more nutritious but higher-cost foods to treat obesity may worsen food insecurity, and providing more low-cost foods to address food insecurity may worsen obesity.

Project NOURISH is aimed at gleaning new insights into the dynamics between food insecurity and childhood obesity and developing effective and equitable community-engaged interventions that will alleviate both issues, starting in early childhood. Very few research projects previously have evaluated the effect of nutrition interventions targeted at food insecurity on child weight trajectory or measured child obesity as a possible unintended consequence.

“What we are trying to do is break the cycle of poverty, food insecurity, and obesity starting at a very young age by combining the strength of our clinical, basic, and translational research teams here at Duke,” Armstrong said. “This is so important right now, with so many children not having enough to eat and so many children with obesity. Chris and I think this is a critical topic, and our research plan could uncover mechanisms and novel treatments that could change the way we look at how we are feeding children and increase their chances for a more equitable and healthy future.”

Engaging the Community

The NOURISH project builds on Armstrong’s career of community-engaged research aimed at helping children and adolescents with obesity. She is chair of the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) section on obesity and co-authored the development of the AAP’s recently released new guidelines on childhood obesity, the first update since 2007.

The new project has several aims and two primary areas of investigation: one a community-engaged clinical research study, the other a laboratory-based basic science investigation.

Armstrong, along with Asheley Skinner, PhD, a professor in population health sciences, leads the first part. Working with randomized cohorts of families who qualify for benefits from food provision programs such as Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), the researchers will assess the impact of two different food insecurity interventions on weight, body-mass index, and other health measures in children aged 12-24 months.

One intervention will provide parents with weekly telehealth call with a dietician who will provide nutrition coaching and work directly with parents to select and provide groceries each week. The other intervention will provide a weekly grocery gift card which will meet the financial need for food, minus dietary counseling.

Armstrong and her team will spend the first year or more building ties within the community, working with families to develop the interventions, and pilot testing processes. Perhaps no aspect of the project is more important than involving the families as equal partners, she said.

“Engaging the community is absolutely critical,” Armstrong said. “We’ll be doing a lot of outreach, teaming up with community-based organizations who share a mission of improving health equity through securing food access and working directly with families to develop solutions that are meaningful and relevant to their lives.”

Feast or Famine

Meanwhile, Newgard heads up the basic science component. He and his team will conduct animal model feeding studies designed to simulate food insecurity conditions, both in types of diet — calorie-dense/nutrient-poor, for example — and in timing of food availability and scarcity. One test group will simulate the feast-or-famine cycle that can result from regular but insufficient infusions of resources.

“With supplemental food programs, the allocation comes in monthly,” Newgard said. “Often it gets spent on calorically dense but nutritionally poor foods when the money comes in at the beginning of the month, and by the end of the month it’s running out and you have an inadequate amount of food. Then the next month starts and you begin the whole cycle all over again. We’ll try to simulate that cycle in our models. We believe we can learn a lot about the molecular circuits that result in this surprising outcome where food insecurity leads to obesity.”

The researchers will apply DMPI’s genomic, proteomic, metabolomic and other tools to analyze the molecular and physiological effects of various food insecurity models.

“Our job at DMPI is to find molecular signatures associated with disease and to figure out why that association exists and what it tells us about the underlying mechanisms,” Newgard said. “That’s our bread and butter. But I don’t think it’s ever been done this way with food insecurity. That’s what we’ve set up here to complement Sarah’s research. We have the right team and great capabilities, and it’ll be all hands on deck to try to figure out what effects food insecurity has at a molecular level.”

Another portion of Lee’s estate gift will fund a project called “Healthy Food, Healthy Life,” conducted by Duke Health & Well-Being and overseen by executive director Scarlet Soriano.

A Healthy Start

The initial NOURISH study is expected to last two to three years, but Armstrong and Newgard both hope their results will leverage additional funding that will allow them to continue the project beyond that.

What they discover about the effects of food insecurity on very young children will help guide next steps and, they hope, provide valuable information about what sorts of interventions are both most effective for children and most feasible for families.

The key next phase, they say, would be to extend the study and continue to track the health and progress of the children beyond their second birthday.

“We very much hope to be able to continue past that,” Armstrong said. “If we can help children start kindergarten nourished and ready to learn, that will overcome so many of the barriers that children in marginalized and poorly resourced communities face today. All children deserve that healthy start to life.”