The Lunch Club

When K.V. Rajagopalan, PhD, arrived in the United States from India to begin his postdoctoral work in the Department of Biochemistry at Duke, he familiarized himself with the department’s members by reading their journal articles. Among them were a series of papers reporting startling research on oxygen radicals by a young biochemist named Irwin Fridovich, PhD’55.

“I said to myself, ‘That work is too outlandish,’” says Rajagopalan, James B. Duke Professor Emeritus of Biochemistry. “I said, ‘I’m not going to have anything to do with that guy.’”

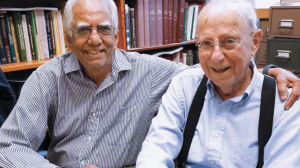

Well, everybody’s wrong sometimes. Fridovich and Rajagopalan have been colleagues and close friends for almost sixty years now. Rajagopalan’s very first project in Durham turned out to be working in the lab of then-department chair Philip Handler, PhD, alongside Fridovich, and Fridovich was co-author on Rajagopalan’s first journal article from Duke. After long and highly distinguished careers at Duke, they are now fellow emeriti faculty members.

“We’re about as emeriti as you can get,” says Fridovich, the James B. Duke Professor Emeritus of Biochemistry. “I’m 87, and he’s not far behind. I like to joke that ‘edentate,’ means ‘without teeth,’ so ‘emeritus’ must mean ‘without merit.’” More than colleagues, they are close friends—so close that for the last fifty years they’ve met to have lunch together five days a week. Every Wednesday, they eat at Bullock’s Barbecue in Durham; the other four weekdays they eat on campus.

“We still have offices here, and we read the journals and keep up with recent work, so we discuss science,” says Rajagopalan. “Along with politics and current events and everything else.” Both men have played outsized roles in the field of biochemistry during their careers at Duke.

Fridovich is best known for his discovery, along with his graduate student, Joe McCord, of superoxide dismutase, a class of enzyme that protects living organisms from the harmful effects of superoxide free radicals that result from the metabolism of oxygen. It was, says, Rajagopalan, “a remarkable discovery,” and it transformed the field; since Fridovich made the original discovery in 1965, some 50,000 papers have been published on superoxide dismutase.

Rajagopalan’s research has focused on molybdenum, an element found in certain enzymes. He made seminal findings into the essential role molybdenum plays in the body— the lack of one molybdenum-containing enzyme leads to a rare but fatal neonatal disease called sulfite oxidase deficiency—and discovered its universal co-factor, called molybdopterin. “The molecule is so unstable that it has never been isolated,” says Fridovich. “Yet Raj and his group successfully determined its structure.

That was a real tour de force. I’ve always considered that an amazing accomplishment.” Handler brought both men to Duke, but they arrived by very different paths. Fridovich received his undergraduate degree from the City College of New York (now the City University of New York) and was working in a lab at Weill Cornell Medical College when his mentor there, Abraham Mazur, suggested that he go to graduate school. “I said, ‘Where do you recommend?’” recalls Fridovich, who came to Duke in 1952. “He said Duke. I’d never heard of Duke, but I said, ‘OK, tell me where it is, and I’ll apply.’ He said, ‘No need; you’ve already been accepted.’ Dr. Mazur and Phil

Handler were friends, and he’d made all the arrangements. All I had to do was show up.” Rajagopalan grew up in India and received his bachelor’s, master’s, and doctoral degrees from the University of Madras. He had never been to the United States, but in reading the journals he knew of Handler’s work and felt the Duke biochemistry department was a good fit for his interest in enzymes.

When he arrived in 1959, many people he encountered struggled with his name—not only the pronunciation of his last name, but also his first name, which is K.V. The letters aren’t initials for anything else.

“One time Raj was ordering something on the telephone,” Fridovich recalls. “The man must have asked him what the K and the V stood for, because I heard Raj say, ‘K only, V only, R-A-J-A-G-O-P-AL-A-N.’ And when the package came, it was addressed to ‘Konly Vonly Rajagopalan’.’”

In 1969, when Handler left to take over the presidency of the National Academy of Sciences, the National Institutes of Health approved the appointment of Rajagopalan as the principal investigator of Handler’s NIH research grant. It ended up being the longest continually funded grant in the NIH’s history, 63 years.

Over the years, both men have considered positions and offers elsewhere. Neither ever bit. Their roots at Duke have grown for half a century, and they run deep; Fridovich’s eldest daughter and all three of Rajagopalan’s sons have Duke degrees.

“We both came here a long time ago and never found any good reason to leave, Duke is home.”

Rajagopalan

Half Century Society Newsletter, Fall 2016

[Photo: K.V. Rajagopalan (left) and Irwin Fridovich]